#GC2022 is accepting submissions - 25d 27h 05m 44s

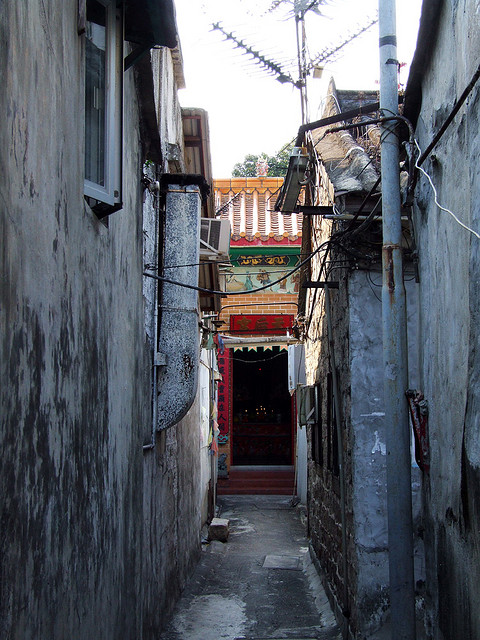

Two and a half years ago, my girlfriend and I were walking through a housing estate near Kowloon City when we happened upon something completely unexpected: a walled village. At first glance, we actually thought it was an old shantytown, surrounded as it was by street hawkers, outdoor barbers and houses made of sheet metal. But as we walked around its periphery, we came across a gatehouse, beyond which was an alley lined by small, tile-roofed houses. At the end was a temple.

"This whole place is going to be gone soon," warned a village resident as we walked through the gate, towards the temple. In turned out we were standing in Nga Tsin Wai, the last walled village in Kowloon. In 2007, the Urban Renewal Authority decided to tear most of it down and replace it with two apartment towers and a heritage-themed park which will incorporate the temple, an ancestral hall and a few village houses.

Returning home, I went online and found that Nga Tsin Wai was established by the Ng, Chan and Lee families in the mid-14th century. At the time, the village was located near the harbour, so in 1352 the families built a temple in honour of the sea goddess Tin Hau. In 1724, walls were built to protect the village from pirates.

Since then, the seaside has vanished, replaced by the Kai Tak Airport, and so have the defensive walls. But the village layout remains more or less the same as it was hundreds of years ago, with three narrow streets and six laneways lined by small tile-roofed houses. Every spring, villagers pay homage to Tin Hau with a festival, and the temple continues to attract donations from villagers and their descendants.

Last month, I returned to the village to see if anything was left. Though a few more houses had been demolished, the village looked more or less the same as when I last visited. It turns out that progress on the urban renewal project has been slow. So far, according to the URA, 65 percent of village houses have been bought. But it's not clear when the acquisition process will be completed and when redevelopment will commence. And even then, nobody knows what the redevelopment will look like — the URA's spokesman told me not to put too much faith in the renderings displayed on the authority's website.

Despite the fact that Hong Kong will be losing a 650-year-old piece of living history, nobody has raised much of a fuss about Nga Tsin Wai, except for a bit of grumbling from the Conservancy Association. In all fairness, it was pretty dilapidated when the redevelopment plan was announced in 2007, and I wouldn't be surprised if most of the relocated residents were happy to move to places with more modern amenities. But it's a sign of the systemic barriers to conservation that exist in Hong Kong that knocking down most of Nga Tsin Wai is seen as the best way to preserve it.

Inside the village

Like most Cantonese walled villages, Nga Tsin Wai is divided by a grid of narrow lanes. The temple sits at the opposite end of the village from the gatehouse. Houses were typically made of stone, with tile roofs, but some were modified in recent decades with sheet-metal additions, air conditioning units and outdoor kitchens. The entire village covers a single acre and consisted of 100 houses before demolitions began in 2007.

On the periphery

Nga Tsin Wai's defensive walls have been replaced by a wall of informally-built houses and shops. Greengrocers line the north side of the village, street hawkers display their wares on the west side and barbers cut hair under plastic tarps on the village's south side. The village gatehouse sits on the east side of the village.

Further reading: Rethinking Urban Renewal in Hong Kong by Christopher DeWolf.

See more photos of Nga Tsin Wai on Flickr. Read more about the village on CNNGo.

This article is originally published in UrbanPhoto