#GC2022 is accepting submissions - 25d 27h 05m 44s

Each year, somewhere in the midst of academic papers and group presentations, within the studio of The Bartlett MSc course in Building and Urban Design in Development the annual fieldtrip is announced, with a mixed atmosphere of anticipation, apprehension, curiosity and excitement about the eminent learning adventure of action-oriented research, and for many students the most formative and enriching aspect of the entire one-year masters course. This past year, Cambodia (co-organised with Asian Coalition for Housing Rights and Community Architects Network) – a remote country, foreign language, chequered history and very much unprecedented in terms of urbanism, is for many of the students a blank canvas to catapult their learning and recalibrate their understanding and approaches to urban design in development.

Cambodia’s urban condition, in the aftermath of the Khmer Rouge regime and the subsequent re-identification with the urban has resulted in an extremely unique set of development processes, both in terms of how the urban is planned and also in how it is manifested and lived on the ground by the Cambodian people.

During the Khmer Rouge regime cities were evacuated, left to deteriorate in the pursuit of an agrarian-based society. Land titles were destroyed, buildings and homes became the property of the state, public infrastructure was sabotaged and urban planning cessed. During the years that followed the civil war, the people of Cambodia slowly picked up the pieces and cities were re-inhabited, urban trajectories were reignited, both out of the shadows of the war and also with a fresh restart without predetermined inertia or direction.

Indeed there were traces of the former bustling centres, in particular in Phnom Penh, today with a population of 1.6m people, it is still very visibly a palimpsest including modern Khmer architecture, French colonial influence, as a historical trading post and as a monarchy base over the centuries. But these remaining physical traces are only a single aspect of the multi-faceted working, living and culture of the city where individuals and collective groups of Cambodians live out their everyday experiences. Intertwined with the formal urbanism of Phnom Penh, although often overlooked and ignored is an informal urbanism. A study in 2014 by Cambodian NGO STT indicated 340 urban poor (informal) settlements in Phnom Penh hold their place in the everyday experiences of over 33,600 families, and in so doing play a part in shaping the city during this time of transition. It is these urban development processes (the informal ones) that interest us most in our research of Cambodia’s urban condition. Layered with the country’s challenges of post-war stabilisation Phnom Penh is transitioning quickly with the vision of being a leading economical power amongst its Southeast Asian counterparts. Industries such as the garment industry are flourishing and inward and rural-urban migration is happening at a pace faster than the city is capable of planning. Foreign (and local) investment is seeing the city landscape change at almost an unrecognizable rate and with a frenzy of haphazard, short-sighted and individualistic objectives. Managing all of these processes and their resulting manifestations is a juggling act for city and government officials, with in some situations power relations and personal interests blurring the path towards an inclusive and liveable city for all of Phnom Penh’s citizens.

Engaging the students in firsthand research experiences in the field or as we sometimes say ‘throwing them in the deep end’ raises a multitude of personal, professional and theoretical challenges which are sometimes more navigable (at least superficially) in remote case studies. We are confronted by the complexities of reality, and for our students in terms of what they experience, how they see their role as practitioners and the position they take when working towards design interventions. When viewing Phnom Penh critically and with a social-spatial cognition one begins to see it is characterised by contradictions;

Housing and land, disproportional distribution – In central downtown locations twenty-something storey condominium buildings sit almost completely empty, and inner city lakes and riverbanks are being filled with sand to generate new high value development sites. Meanwhile many urban poor are forced to live on the periphery of the city in substandard conditions (some as a direct result of the inner city redevelopment projects), and with long and costly commutes to city centre jobs.

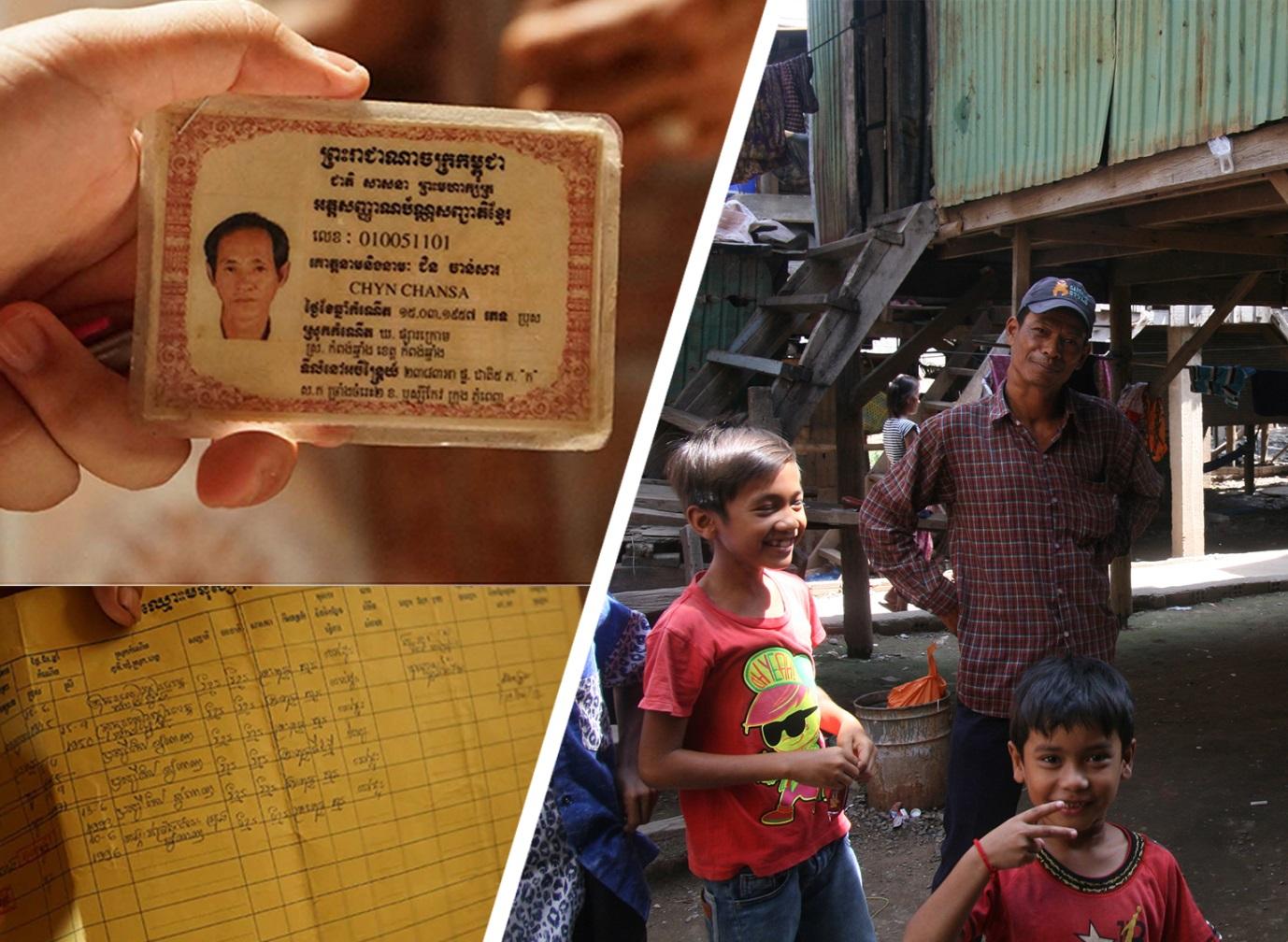

Land titling, caught between the rules and the reality – When land titling was reinstated new government policies were put into place which continue to be in place today. Simply put, once a resident has lived in their home for five years (with specific proof and paperwork) they are entitled to a land certificate, paving the way to a land title. This in turn should bring housing security, entitlement to public services and infrastructure, build a sense of citizenship and encourage people to maintain and improve their housing and living environment. But, many urban poor are discovering these policies and their processes are not being fairly and reliably enforced leaving many urban poor in vulnerable situations without legal housing or access to services, and with an overarching sense of uncertainty and despondence, even after proactive citizenship and a conscious effort to work within the existing policy framework.

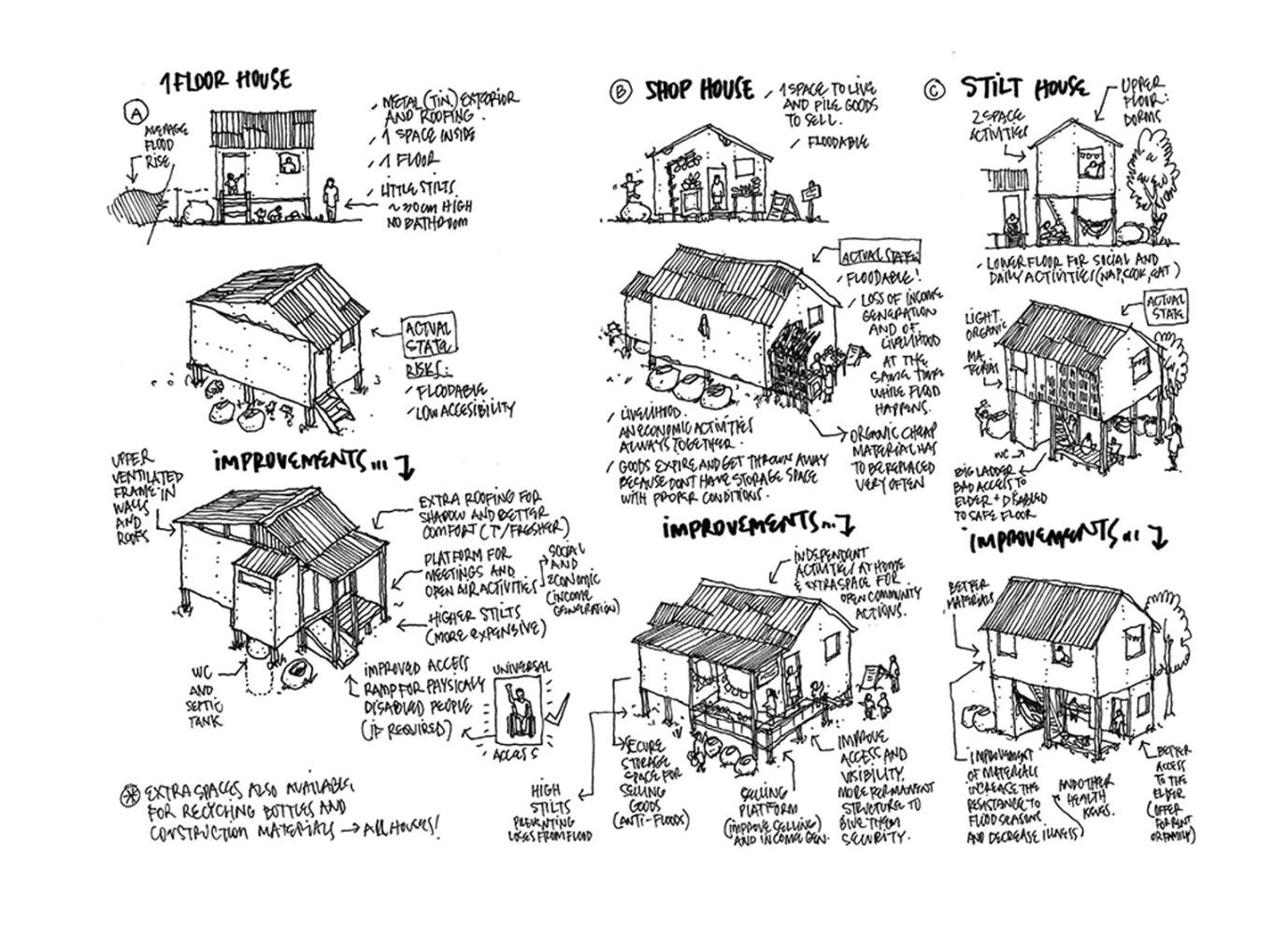

Urban living conditions and vibrant neighbourhoods – In areas across the city, informal neighbourhoods have sprung up as a response to rapid urban migration and development, as the formal sector and city infrastructure and planning have not been able to meet the demand for housing. Overtime, many of these settlements have become vibrant social and economic hubs, with strong interdependence between the formal and informal city. Instead of embracing the positive nature of these places and helping to improve the ongoing challenges such as sanitation, water and overcrowding, swathes of people have been evicted to relocation sites which not only lack proper sanitation water and shelter, basic human rights, but also dismantle social structures, thriving informal economies and isolate workforces, all under a rhetoric of improved living conditions and urban regeneration.

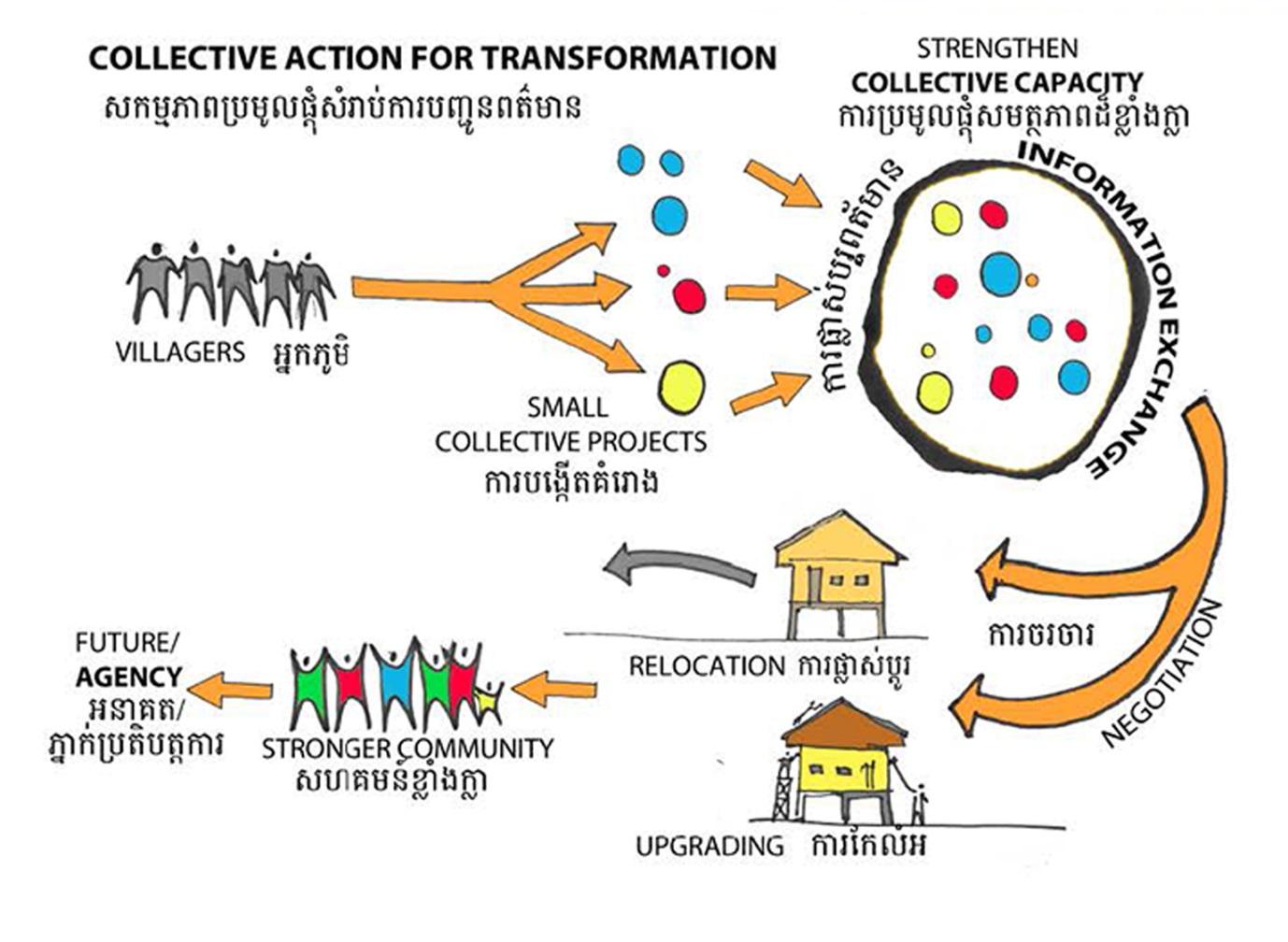

Active participants in shaping the city – Initiative and innovation is ripe in the (informal) city, with many with limited resources taking an active role in improving their living conditions, taking control of their social networks and safety nets, and continually expanding their livelihood potential. Sometimes these developments are done slowly, incrementally, and in subtle ways, but none the less, a positive and active role in city development from the ground up. In other areas of the (formal) city there is a very different; top-down, limiting, disengaged and disempowering production of the city taking place. Where the provision of social/public housing is disjointed from livelihoods, needs and aspirations are perceived as uniform, and residents are disconnected to the development process often seen more as recipients rather than active participants.

It is through these types of contradictions that we realise that we can no longer solely rely on mainstream knowledge, design practice and education, and instead we search for the opportunities for strategic interventions in our role as development practitioners, in an effort to use the urban design practice as an activator for change, and to rebalance, recalibrate, and reshape the processes of urban development within the city. Unlike conventional built environment design courses, the BUDD course aims to move beyond the aesthetics and objects of design. Through a process of unlearning these modes of practice, we hope to identify opportunities for allowing new processes of urban development which fully engage the urban poor in the city’s transformation.

Our journey to Cambodia doesn’t start and stop at Heathrow Airport London, nor is the experience limited to the students and staff of the BUDD course. The BUDD fieldtrip is situated within a yearlong academic practice module of (design and research) work and (learning) initiatives and within a long-term engagement with the Asian Coalition for Housing Rights (ACHR).

Within the course, the fieldtrip is subsequent to a short international excursion in critical design and a case study project. While in the field we adopt the concept of ‘flexibility’ as a first step in situating ourselves within the place, time, culture and everyday day live of Cambodia. Nothing is fixed clear or linear, we are quick to realise that design in these recalibrated modes is collaborative, negotiated, process-oriented, messy, provisional and complicated.

A key vehicle for the research is through exploring local sources of knowledge and information. Overarching the fieldtrip are strong and ongoing links with local partner organisations (ACHR and CAN) with an established commitment for at least two to three years. In the field we are never alone in our learning and research – whether it be workshops, interviews, focused discussions, observations or translations (linguistic and cultural understandings) with urban poor people, local students, local authorities and local development practitioners we are immersed in our work, progressing towards answering our research questions, and the questions set out by the communities with which we are working; and in both cases, leaving space for new twists and unexpected discoveries. Our encounters and the students concluding reports are both part of a legacy, towards normalising alternative modes of urban design, architecture, and development, and building the capacity and inertia within people to work through these alternative modes of production.

Taken straight from one of the students’ report titles grounding transformation is what our students experience through the fieldtrip part of their learning process. By working directly with urban poor communities and with the non-conventional perspective nurtured through the studio they are enabled to identify alternative transformative potentials, offer critical design ideas, and envision a radically different city. Following are some pieces of student work produced this past May while in Cambodia and as part of their concluding research reports, some offer a means to an end while other proposals serve as a catalyst for further developments and manifestations.

The pedagogical approach of critical design within the studio and specifically how it’s played out within the fieldtrip project addresses design challenges from the perspective of the community and offers the possibility to work holistically on real life challenges and contradictions, as those we experienced in Phnom Penh. The 3-part process of studio case study, short international excursion and fieldtrip are beyond a linear process, where at each step the critical thinking and understanding is progressively opened out cumulatively, uniting theory with the complexity of the challenges and opportunities to the point of reality, our fieldtrip to Cambodia. Continually, students are challenged to refuse to be seduced by conventional thoughts and straight forward answers, taking their understanding of ‘design interventions’ beyond only physical structures (embracing social and political mechanisms) in order to address spatial problems and allowing people to play a key part in realise transformative potential within their city and within their everyday lives.

The student’s full reports are available on the BUDD section of the DPU website.

/////////////////

Jennifer Cirne is a teaching fellow at The Bartlett Development Planning Unit DPU, University College London. Photos via author unless otherwise linked.